Lia Cook

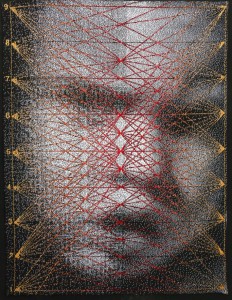

I work in a variety of media combining weaving with painting, photography, video and digital technology. My current practice explores the sensuality of the woven image and the emotional connections to memories of touch and cloth. Working in collaboration with neuroscientists, I am investigating the nature of the emotional response to woven faces by mapping these responses in the brain. I draw on the laboratory experience both with process and tools to stimulate new work in reaction to these investigations. I am interested in both the scientific study as well as my artistic response to these unexpected sources, exploring the territory between in several different ways.

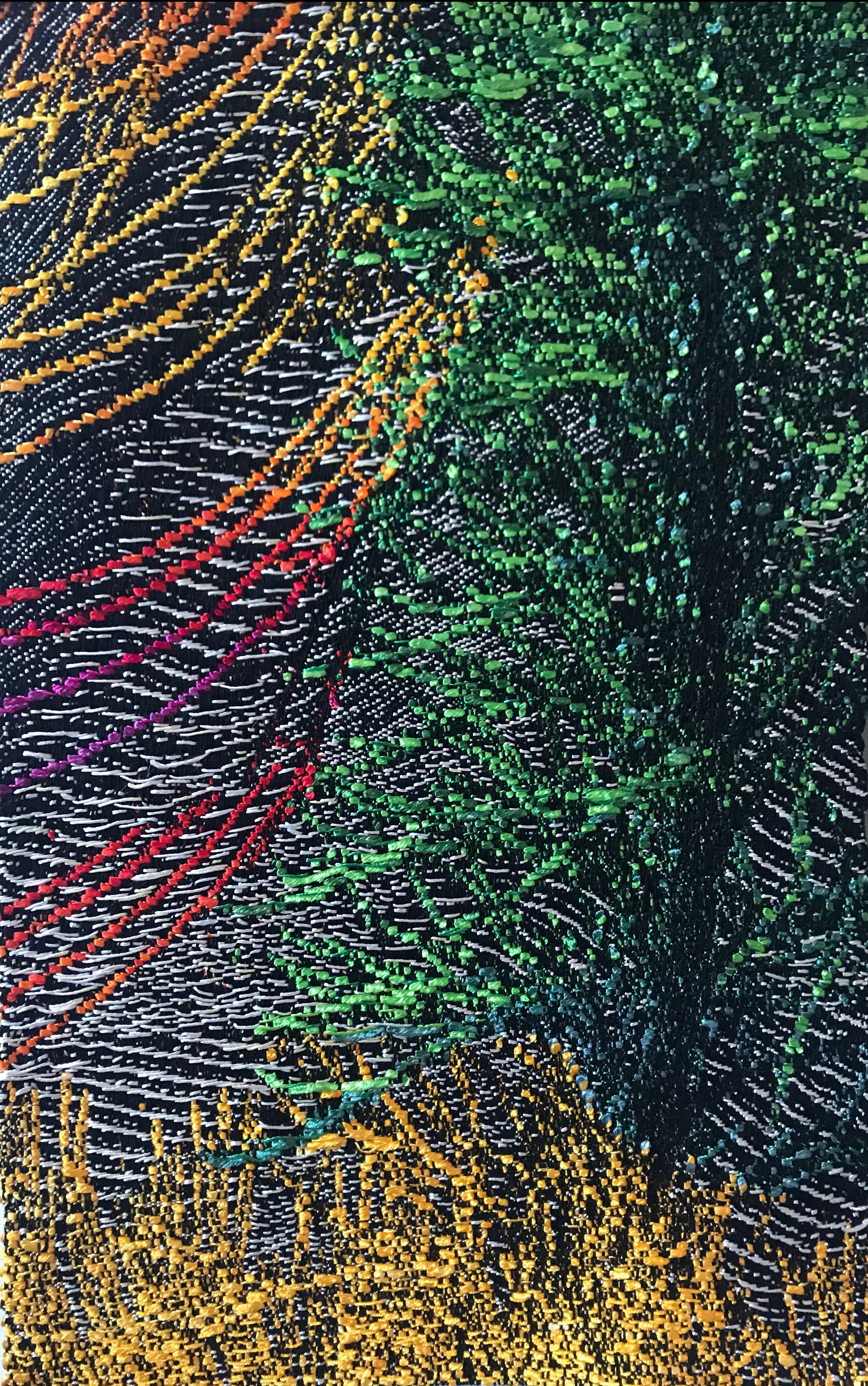

In my work I have used DSI (Diffusion Spectrum Imaging of the brain) and TrackVis software from Harvard to look at the structural neuronal connections between parts of the brain, and integrate these “fiber tracks” with the actual fiber connections that make up the woven translation of an image.

In some of my exhibitions, I collected and analyzed data through a participatory behavioral study, in which my audience engaged directly with the work and recorded their responses. In recent pieces, visualization of this data is woven back into the work. (More about Data Visualization Research: summary and full study)

In the ongoing project “Su Series,” I explore how the physical translation of an image as well as its material substance informs the emotional experience of the work. Using the same face over and over again, I translate it differently each time through weaving; the subtle and dramatic variations create vastly different emotional affects.

My new interest is to explore integration of my earlier work with my current inspirations. I combine neurological brain fibers, plant fibers from my garden, and woven optical lines and patterns drawn from past weavings. I use my immediate environment to generate new very tactile and intimate works.

Three Fibers Integrate (2020) is a recent piece that continues a new interest to re-envision my early work from the 1970s with my current inspirations.

Watch a video introduction and short studio tour

Oral History Interview with Lia Cook (2006) – Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Quotes

[The psychological jolt of Lia Cook’s Traces Past]: This large jacquard tapestry is made of woven cotton and rayon. In a series of moody/creepy depictions of doll faces, the Bay Area-based Cook explores emotional connections to memories of touch and cloth. She recently began using diffusion spectrum imaging of the brain, integrating th physiological fiber connections to actual fiber connections that are delineated in a woven image. The result: a softly haunting image that stirs an almost primordial, visceral response.

— Donald Munroe, online review of exhibition “Fiber Art Master Works” for The Fresno Bee, 2016

Lia Cook translates a photo of a child’s face into a monumental tapestry. It hangs from the ceiling just to the right of Rosen’s birds. The enlargement should, by all rights, make it less intimate; but the warp and weft of it produce the opposite effect, turning the grain (or perhaps digital noise) of the source image into a maze of interlocking markings, reminiscent of Bruce Conner’s obsessive drawings, now on view at the San Jose ICA.

— David M. Roth, online review of exhibition “Material Matters” for Web magazine Square Cylinder, 2015

In a review of a later show for the journal Textile, I described my first encounter with Cook’s work:

‘Approaching one piece after the next, I became acutely aware of how the woven construction of the image frustrated my attempts to resolve that image. At a certain distance I could only see image, not thread. At another distance I could only see thread, not image. Standing at the precise threshold demarcating these two possible views of the work, and rocking first forward then back, I found that the resulting perceptual confusion released a particular affective response – something in proximity of grief or longing though not exactly either of those. Something that in a story would be evoked by the word ago.’ (Leemann, 333)

It is a common experience among viewers of Cook’s work—this intense affective response—and it is one that will be entirely misattributed by anyone viewing documentation of her work on the page or screen. The still image deceives—it pretends the work is singular, it pretends the work is fixed, stays the same. With performance and other live art forms, we know that documentation is unreliable and cannot produce what the work itself produces. But with an essentially flat, frontally viewed image/object we think the photo of the work essentially does what the work itself does. But with Cook’s work this isn’t the case. And why it isn’t the case is at the heart of what her work does, of how it behaves.

The candid intimacy of the family snapshot seems an unlikely starting point for Lia Cook’s over-scale woven images, until one considers that such weaving, whatever its size, is the result of the organisation of small elements, close attention to detail and the dexterity of handwork. Just as informal family photos are a medium of transaction and an exchange of intimate information and shared history, cloth enfolds us into its history as we allow it to envelop us and record the marks and creases of our presence. The source of Cook’s images is a simple camera from the 1950s, which has a link to today’s imaging technology in the same way that computers have their origins in the manually operated Jacquard weaving looms of the early nineteenth century. In Big beach boy Cook links these technologies, exchanging pixels for thread and focusing closely on the bland subject matter of a tiny and apparently insignificant family photo of a baby. On closer inspection, when we seem to be skin-to-skin with the child in an uneasy embrace, the subject dissolves into a pointillist colour field of shimmering individual threads, allowing our senses to take us beyond the threshold of recognition.

— Robert Bell, Curator, National Gallery of Australia, Web text for exhibition “Transformations: The Language of Craft” 2005

The viewer is struck by the sheer physicality of her art as well as by her intellectual engagement. Sensual and sumptuous these….. works… spur questions and concerns that bring down the curtain on conventional notions regarding painting and privilege.

— Miles Beller, review of “Material Allusions” traveling exhibition, in Artweek Magazine.

Absorption and inclusion are pervasive strategies in Cooks work, operating at almost every level: formally, in her constant exploration of new techniques; emotionally in the way she stimulates the sense of touch through the eyes; and intellectually in the multiple reference to different art histories. Her work reminds us that in English the phrase “to weave together “ means “to integrate.

— Meridith Tromble, essay for the Flintridge Foundation Awards for Visual Artists 1999/2000 catalogue.